|

It was 1958 when Walt went on a trip to Switzerland in order to help get started on the new live action film, Third Man on the Mountain. Before leaving, he stopped by one of his imagineers, Vic Greene. “Vic,” he said, poking his head into the office door. “I want you to get brainstorming on some new attractions to put in Tomorrowland. Something big. We’ll talk more about it when I get back from Switzerland.” When Walt arrived, he and director Ken Annakin took a train to the little town of Zermatt which has an amazing view of the Matterhorn. Walt was entranced. He rushed into a gift shop and purchased a postcard with a picture of the Matterhorn on it and on the back scrawled a simple message: “Vic, build this! Walt.” The day the postcard arrived in Vic’s office, he started designing. Walt moved on to Germany and became interested in the bullet-shaped trains that rode around there. In turn he had another idea for a train much like them - a monorail. Finally, though, Walt had one more ride that he was brainstorming. Following the success of “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea,” Walt wanted to take people on a Submarine Voyage. With this three attractions in mind, Walt returned home and hit his first speed bump - his own brother Roy. Roy didn’t want any new rides until the Disney company was out of the debt that Disneyland put them in in the first place. Walt tried to convince him but Roy was immovable. In a couple of years they could think about it, but not now. After the end of the argument, Roy left to Europe to try and gain some foreign investors. Meanwhile Walt called together his imagineers. His opening statement was right to the point, “We’re going to build the Matterhorn, the Monorail, and the Submarines.”

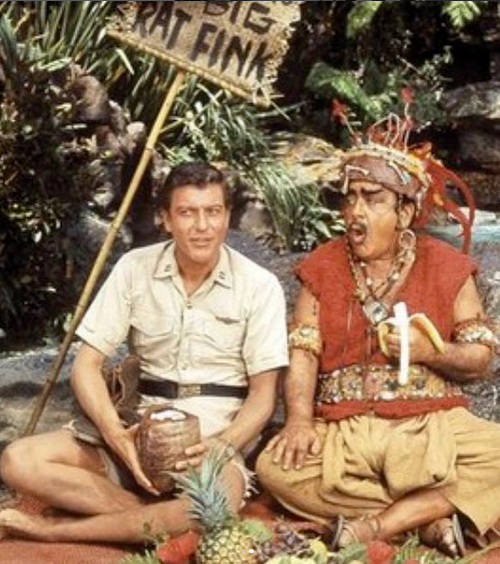

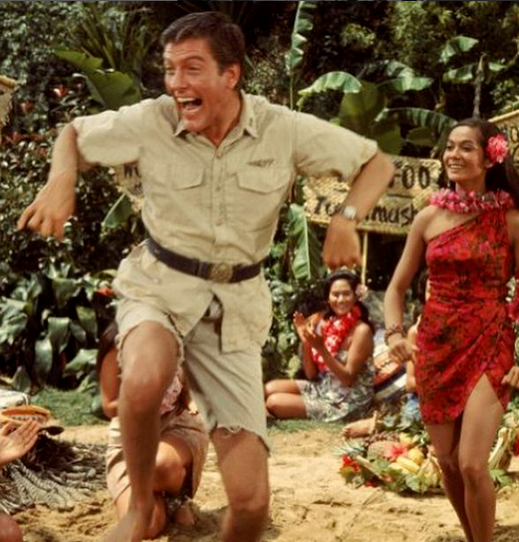

The imagineers were already well aware of Roy’s opposition to the projects. “What will Roy say?” one of the imagineers at the table asked. “Don’t worry about Roy,” Walt said. “We’re going to build ‘em. Roy can figure out how to pay for ‘em when he gets back.” Walt might have had to go behind Roy’s back, but thank heavens he did because those three rides were sensational when they opened. Sometimes Walt was the only person to see the bigger picture. The idea for the 1966 film Lt. Robin Crusoe, U.S.N. came to Walt as he was on an airplane. The story was loosely based on the book Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe, but with many changes. For example, Friday (Crusoe’s companion) was turned into a monkey. And there is much more interaction with native tribes than in the original story. Above it all, the story was modernized so that Robin Crusoe, played by the hilarious Dick Van Dyke, was in the United States Navy. Walt wrote the idea for the story on a piece of paper and brought it to the studio. When the movie was made, he demanded credit for the story and so in the credits, a line reads “Original Story by Retlaw Elias Yensid,” which just so happens to be his own name backwards (except for his middle name.)

You could always count on Walt to focus on the little details which added fun and wonder to everything he did. After Disneyland opened, Walt always wanted to know how to make the experience better for his guests. So, oftentimes, he would dress up in normal everyday clothes and wander the park like a guest and even wait in lines for rides, striking up conversations with the other park goers. He asked what they liked or what they thought could be improved. He would also always carry a wad of $5 bills in his pocket and would slip a bill to an employee as a bonus whenever he saw them "plus-ing" the experience for others. Occasionally he would even work in the ice cream shop on Main Street.

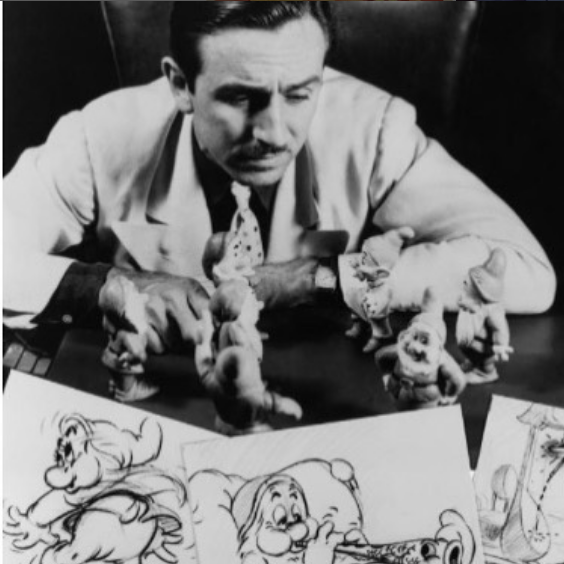

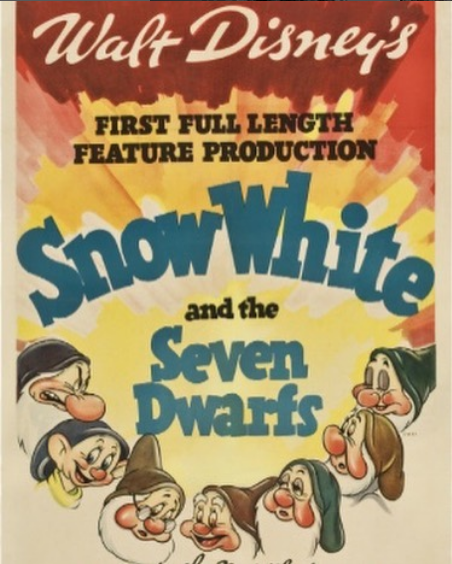

Walt was all about “plus-ing” the experience for people. He always was trying to make things better and if he could make just once person smile, then he would consider his day a success. In 1934, Walt decided to take his biggest gamble yet - a full length feature film that was completely animated. Lily was shocked that her husband would even think of it. “Walt,” she told him. “the short subjects are doing well! The studio is successful! Why risk everything on a movie that could ruin us?” Roy, equally skeptical about the idea, was worried about how much that would cost. At that time, the cost of creating a seven minute technicolor cartoon was approximately $23,500. A feature length film, Walt figured, would be about twelve times that length. In the end, Walt estimated a budget of $250,000 for the movie. Roy, knowing Walt’s history of over-optimizing their budgets, put the cost at around $500,000. Despite his wife and his brother telling him no, Walt had no intention of giving up on this new venture. A few days later, Walt called together forty of his top animators. He pulled out his wallet and handed them some cash, saying, “I want you fellas to go have dinner and relax a little. Then come back to the studio. I have a story to tell you.” The animators left and when they returned they found Walt standing on the recording stage surrounded by a semicircle of folding chairs. The room had been darkened until only a single lightbulb shined down on Walt, who stood bouncing on the balls of his heels, ever the showman. Once everyone had taken their seats, Walt began to not only tell, but perform the story of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. With every new character, he would act out the part to the letter, making the proper facial expressions. He would skew his features and arch his eyebrows as the queen, and tilt his face just right so that the light gave him the pale innocent complexion of Snow White. When Walt finished, he said, slightly breathlessly, “That is going to be our first feature-length animated film.” If he had said those words before performing, no one would have been on board. But the fact that he showed them it would work and that they were able to see the story before their very eyes — everyone joined in the idea with full enthusiasm. All because Walt knew how to lead. But it wouldn’t come without hard work. He sent his animators all to art school to learn to draw what he needed for the film. He had to ask for loans to pay off the film. Yet behind his back the distributors were laughing at him, calling the project “Disney’s Folly.” When Roy told Walt that people were talking about the film in such a way, Walt replied confidently, “Let them. All that talk is doing is generating more buzz about the film.” When the film premiered on December 21st, 1937 at the Carthay Circle Theater, it was a huge hit, earning $8,000,000 in its first release. “Disney’s Folly” became a thing of triumph! The Disney Studios corporate offices are held up by the seven dwarfs because the company was built on the success of this first even animated feature film.

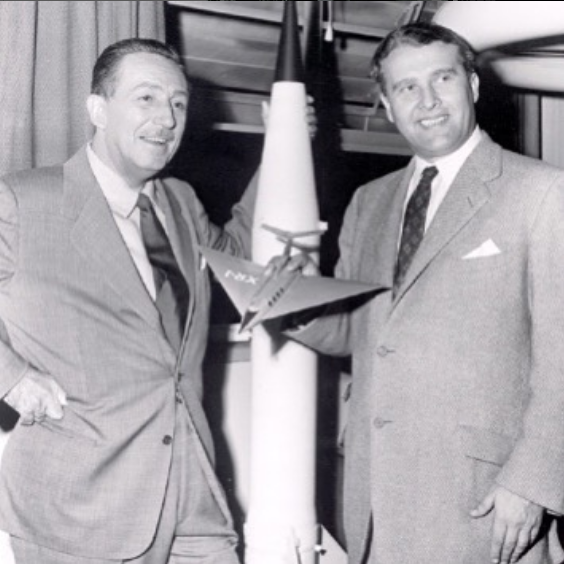

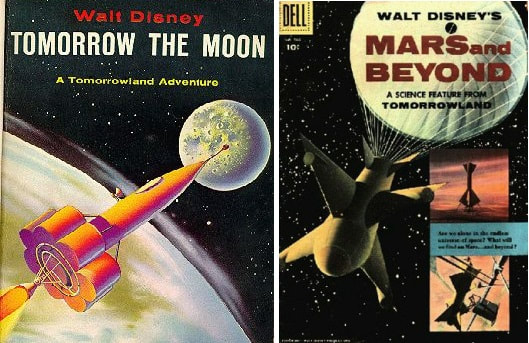

In 1953, Ward Kimball showed Walt six articles from Collier’s magazine that had been penned by scientist Wernher von Braun, Willy Ley, and others, and introduced a plan for a fully functioning space program. Walt was enthusiastic about the idea and contacted Wernher bon Braun and asked to meet with him. Von Braun was a brilliant scientist who worked with the nazis during WWII to develop the V2 rockets. Nevertheless he was not sympathetic to “Hitler’s war” and at one point was arrested by the gestapo for suggesting that rockets could be used peacefully to colonize the moon and other planets. After the war, he emigrated to the US and became one of the most influential members of the space program. Walt asked von Braun to act as technical advisor to a special program he was deciding for the Disneyland TV series and von Braun excitedly agreed. Knowing that Ward Kimball was highly interested in all things space, Walt asked him to produce and direct the coming space episode. Charles Shows would write the script. They spent weeks on the project, researching and writing until finally they showed Walt a finished product for what they planned on calling “Man in Space.” It would begin a thousand years in the past where ancient Chinese invent the first rockets then travel ahead into the future where man develops space stations and astronauts explore the moon and mars. When they finished, Walt didn’t speak for several moments. “You know, boys,” he said finally, “you don’t have a story here.” Kimball and Shows felt their hearts drop into their stomachs. “We don’t have a story?” Shows asked. “You have three stories,” Walt insisted. “Three different episodes. The first should be called ‘Man in Space,’ about the development of rockets and manned spaceflight. The second should be on how to put the first men on the moon. We’ll call it ‘Tomorrow the Moon.’ The third will be on Mars and the search for life beyond the Earth. We’ll call it ‘Mars and Beyond.'”

The episodes went on to become so influential that Dwight Eisenhower even requested copies of it to show his staff. Walt was an optimist and a futurist. He not only dreamed of the future, he did everything to make it happen. |

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed